The [Land Value Tax] strikes at the heart of the land monopoly. In a powerful speech, Winston Churchill said, “Land monopoly is not the only monopoly, but it is by far the greatest of monopolies — it is a perpetual monopoly, and it is the mother of all other forms of monopoly.” It is the essence of feudalism and for all of our supposed social progress we’ve yet to be free from it. Unless and until the land monopoly is destroyed, the positive effects of virtually all economic reforms and even philanthropy is largely nullified. (Edward Miller, “The Only Economic Reform Worth Talking About“)

The Only Economic Reform Worth Talking About is, according to Miller, a shift to a Land Value Tax (a kind-of straight tax on the land itself, regardless of “property improvements” – also known as natural rent). Another way to think about this is not so much as a tax on land owners, but we the people charging rent for use of the commons.

It’s an interesting notion. I’m trying to reconcile it with the notions I’ve expressed before about taxing the bad stuff rather than the good stuff. So I’m wondering, is land ownership bad stuff to be taxed, or good stuff to be incentivized?

I’ve heard the proposition that the best way to protect land is to have it owned by someone in perpetuity and pass it to their descendants, so that they have an incentive to steward it in ways compatible with its long-term viability. The Nature Conservancy does most of its work by purchasing land in order to protect it, and it does seem to work in this system. But I’m far from convinced that it’s the only way to protect land, or even the best option.

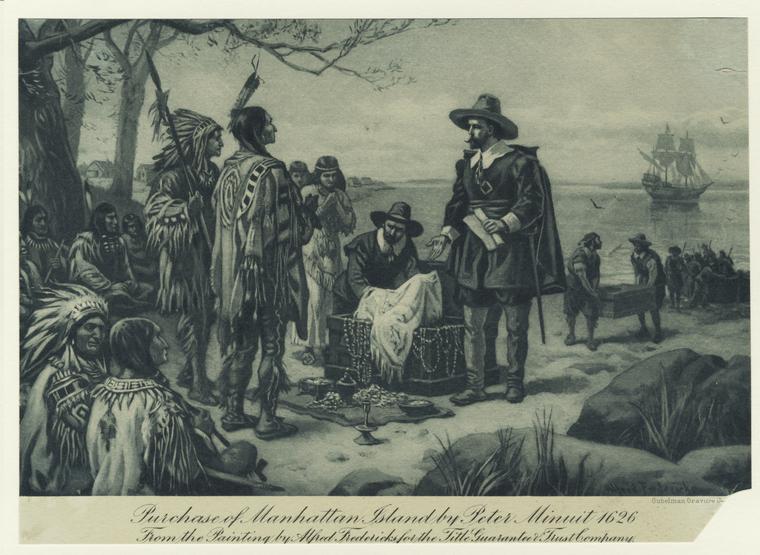

[Sam: ]”That’s the kind of thinking that got Manhattan sold for a box of beads.”

[Coyote:] “So they still tell that story? It was one of my best tricks. They gave us many beads for that island. They didn’t know that you can’t own land.”

(Christopher Moore, Coyote Blue )

I’m a little more comfortable with rent than ownership, I suppose. So, how would charging rent to any and all land tenants help the cause of sustainability? Could this facilitate both greater equity among people and better stewardship of all the land and all its denizens (especially the non-human ones and the generations not yet born)? Can we up the rent on those whose stewardship neglects these considerations?

In the money culture, will a Land Value Tax encourage care and protection of the living world while providing equitably for the people (present and future) who depend on it?

Your article shows a good understanding of the core issues. Indeed, the slogan “tax bads not goods” is often used among people who believe in this issue.

Dave Wetzel is one such person who was heavily involved in the congestion pricing program in London under Mayor Ken Livingstone. Also Frank de Jong, the original leader of the Green Party of Ontario, is extremely active on this issue.

I met both of them a few days ago at this conference:

http://cgocouncil.org/conf11.htm

Where they were literally handing out buttons to every attendee that said “tax bads not goods.”

Now, as far as the details go, one of the primary benefits of Land Value Taxation would be to sharply curtail urban sprawl. Urban sprawl is only possible when land is cheap to own, because otherwise higher density development would commence.

Books like “Green Metropolis” have looked at the topic of urban density at length, and shown how it can be far more efficient than the most hardcore eco-village.

The trick is that with high enough density, the need to own cars evaporates. 80% of the residents of manhattan do not own a car. Most live in high-rises which allow them to share one heating and cooling system, which dramatically increases efficiency. If you are just heating your home, the heat that escapes above your home just moves into the atmosphere, whereas in an apartment it rises to the floor above.

Every vacant or underdeveloped lot in a city forces sprawl, but that is primarily a result of government policy. There is this term “gentrification,” which is relevant. When the community makes investment into a region, perhaps by undertaking a large public transportation project, then the land values rise, and so people avoid those areas and seek nearby areas with cheaper land values.

Then these new communities begin to gentrify and eventually demand similar infrastructure projects at a great expense, even though the first infrastructure project would have been able to support them just fine if only they could afford to live there. Rinse and repeat.

Every bit of density in a city is one more area that can be freed up for nature. People don’t like urban sprawl, they want to live in the denser areas because there is more to do, they just can’t afford it. Even despite all the vacant lots.

LikeLike

I want one of those buttons 🙂

I’m a huge fan of New Urbanism/Smart Growth, for many of the reasons you state, and a few others, like the improved capacity for innovation at higher densities of intellectual and creative types (c.f. http://www.creativeclass.com/rfcgdb/articles/Beyond_Spillovers.pdf). As you point out, high-density human populations are often much ecologically preferable to sprawl (especially for car-free-by-choice folx like myself).

I guess I’m not seeing the line between that, individual land ownership and the LVT all that clearly (3 dots – how do they connect?). After all, I believe urban high-density dwellings are usually apartments (landlord/tenant relationships and and all that, so I guess that the landlord would be taxed on the parcel where the building sits), or condos (with some arrangement of a homeowner’s association being responsible for the land, and condo owners responsible for the interior space of their unit). So the landlord or HOA would be subject to the LVT, and that cost would likely be passed along to tenants. In either of these arrangements, the “landholder” could be, instead, a government (municipal, state, federal) or some community cooperative agreement, with little to no necessary change in how green the community is or how affordable the rent is.

I just don’t grok the argument for ownership here, and it seems that the LVT is dependent on individual ownership. I suspect I’m missing something.

LikeLike

The incentives of the current system occur regardless of what urban planning program is implemented. As long as the tax structure and land tenure system remain as they are, then the incentives for sprawl will continue. That is one of the main reasons why New Urbanism is a failure, and always will be a failure, despite the best of intentions.

The only way to achieve the goals of New Urbanism is to change the low-level incentive structures that create sprawl in the first place.

As far as who really owns the land under an LVT system, it is primarily the community. The landlords of today would be functionally leasing out their land from the community as a whole. The titleholders can retain a piece of paper that says “land title” on it, but the fruits of nature which that title affords are primarily going to be recaptured by the community.

When the US originally sold off its public lands, it did make a mistake. Instead of selling off eternal rights to the land, it should have leased it out on an annual basis. Most of the US’s original revenue was from tariffs and land sales. If it would have leased out the land, it never would have needed income taxes or any other taxes… and indeed it could have ended tariffs too.

LikeLike

Check out this guy’s blog

http://renegadeecologist.blogspot.com/

LikeLike